The trial of Jesus Christ before the Roman governor Pontius Pilate is the most famous trial in human history. One of its most fascinating aspects remains somewhat of a mystery: Where was it held in Jerusalem?

Three of the four Gospels contain some helpful clues to the trial’s location but they do not mention a clearly identifiable site in Jerusalem.

For instance, Jesus was taken to Pilate’s judgment hall—the Praetorium (Matthew 27:27; Mark 15:16; John 18:28). In this context, a Praetorium was the governor’s headquarters with its accompanying military escort and encampment.

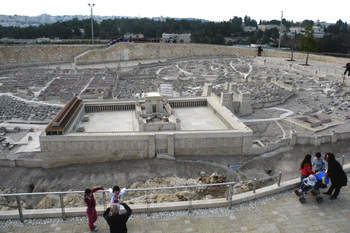

Roman soldiers in the governor’s service usually were housed at two locations in Jerusalem—at King Herod’s Palace/Fortress Antonia near the Temple and at an encampment within or near Herod’s Palace Complex at the western edge of the city. The Gospel of Mark seemingly identifies the Praetorium within one of these palace complexes (Mark 15:16).

In addition, the Gospel of John reveals that Pilate brings Jesus outside the palace proper, sets up his judgment seat on a stone pavement (perhaps in the courtyard of the palace complex or just outside it), and conducts the rest of the trial in front of some Jewish leaders who had refused to enter the palace (John 18:28; 19:13). The stone pavement (“gabbatha” in Aramaic) is thought by some to be a useful clue in solving the location of the trial.

So which of King Herod’s Jerusalem palace complexes provided the locale for the trial of Jesus?

Both locations possess a long history of advocates, dating back to when Jerusalem became a Christian city during the reign of Constantine in the early fourth century. When Christians began to map out the route Jesus took from the trial to His execution at Golgotha (the Via Dolorosa—”the Way of Sorrows”), different routes emerged throughout the centuries that included the two palace locations.

Trial site: Fortress Antonia

Today virtually none of the fortress exists above ground level. Nevertheless, the current official route for the Via Dolorosa begins near the Sisters of Zion Convent where pilgrims are shown the “stone pavement” thought to be the paving stones of the Fortress Antonia where Pilate pronounced judgment on Jesus. Support for this site has included the thought that Pilate wanted his headquarters near the Temple for the heavily trafficked Passover week. Nervous Roman governors worried that crowds visiting the city during this time possessed a greater propensity for civil unrest.

Conversely, the site appears to be an unlikely location for the trial of Jesus. While today’s route for the Via Dolorosa begins here, this specific route only dates back to the 18th century (although other previous routes have included this trial site from time to time).

Author Herbert Thurston has documented the evolution of the various Via Dolorosa routes over time in his work “The Stations of the Cross.” Moreover, archeologists have confirmed that the famed “paving stones” at the site actually date to the Roman Emperor Hadrian’s construction of a pavement during the second century. Hadrian paved over the Struthion Pool for a forum he built in this area.

During Pilate’s administration of Judea, this site, although adjacent to the Fortress Antonia, would have been underwater, archaeologist Pierre Benoit noted in his book “Antonia Fortress.” Although Josephus confirms that Roman troops were stationed in the Antonia (Jewish War, 5,238-247), no ancient sources have specifically stated that Roman governors maintained their headquarters at this particular site. Little reliable evidence exists to confirm the Fortress Antonia as the site for the trail of Jesus.

Trial site: Herod’s Western Palace

The more probable site for the trial of Jesus before Pilate was in King Herod’s magnificent Palace Complex on the western side of the city. While Roman governors of Judea usually were stationed in the coastal city of Caesarea, they stayed and conducted business in this palace when they visited Jerusalem (Josephus, Jewish War, 2,301-8; Philo, Embassy to Gaius, 306).

This palace was more spacious and more elaborately furnished than the palace within the Fortress Antonia—thereby a more fitting residence for a Roman governor. Additionally, the extensive courtyards of the palace complex and nearby fortified towers with its apartments provided space for soldiers to encamp (Jewish War, 2,329).

Recent archeological excavations have uncovered other information about the site. Archeologist Shimon Gibson uncovered some raised pavement stones in 2009 near the site of Herod’s Western Palace that were thought to have been the “gabbatha” mentioned in the fourth Gospel. Gibson has endorsed the belief that Herod’s Western Palace was the location for the trial of Jesus (WORLD News Service, Jan. 9, 2015).

In January, Israeli archeologist Amit Re’em announced the results of years of excavations in and around this palace. Under an old Ottoman (Turkish) era prison, foundational stones have been uncovered, along with an extensive sewer system and related waterworks that once were part of Herod’s palace. Tours of the excavations have been opened to the public and Tower of David Museum director Eilat Lieber hopes that Christian pilgrims will add the site to their holy land visits.

Perhaps the only drawback to completely endorsing this location as the site of the trial of Jesus before Pilate remains the silence of the four Gospels regarding the specific locale for the trial.

Less than 40 years after the trial, both of Herod’s fortress palaces in Jerusalem were destroyed in the Jewish Revolt at a time when early copies of some of the Gospels were being circulated. Readers and hearers of these written works could no longer relate what they heard or read with the physical above-ground remains of the doomed city. To a certain extent, then, some uncertainty about the venue of the trial of Jesus continues to this day. (BP)

Stephen Douglas Wilson is an adjunct professor at West Kentucky Community and Technical College and a former member of the SBC Executive Committee.

Stephen Douglas Wilson